Are You Spreading Sh*t?

“Among mortals second thoughts are wisest." — Euripides

Who are you? Why are you reading this blog? Moreover, why did I even write it?

All questions I asked myself after listening to a recent episode of the New Books In podcast, during which David R. Brake discussed his book, Sharing Our Lives Online: Risks and Exposure in Social Media.

During the episode, Brake highlights some of the harms that can arise from unwary social media use and explains the social, technological, and commercial influences that keep us posting what we often shouldn’t and prevent us from appreciating the risks when we do so.

Although he mainly focuses on issues around managing our professional image, much of what Brake had to say resonated with me in terms of topics I've covered in other blog posts, most notably our need to be better at critical thinking and filtering out bullshit.

In particular, the podcast led me to consider the flip side of this: rather than just filtering the information we are exposed to and might 'consume', how well do we police what we ourselves broadcast and share online?

Are we (perhaps unwittingly) contributing to the spreading of bullshit, and what impact could this be having on the learning of others? More to the point, should we even care?

Five specific aspects of what was discussed stood out

1/ Brake highlights the role that technology plays in making it as easy as possible to communicate and share information.

However, the use of this technology takes place in an environment where companies and marketers have specific agendas and commercial imperatives for us to actively share as much stuff as possible; they want to maximise sharing, not necessarily optimise sharing.

For example, Facebook's business model, and the way the platform is structured are about getting us to share as much as possible as often as possible. This isn't necessarily to ours or society's benefit, but to the benefit of Facebook and the advertisers they subsequently market our 'data' to. Brake suggests that sometimes these interests align, sometimes they don't; either way, most people do not consider this agenda when they post. Do you?

2/ Aligned to this, Brake suggests the word 'share' itself is a loaded term - we don't say "reveal stuff about yourself" after all.

Moreover, the presenter of the podcast wonders whether there is a subtle (but potentially influential) difference between a 'publish' button and 'post' button, suggesting 'post' sounds like a sticky note and therefore fairly harmless (likewise, 'tweet' sounds quite innocuous), whereas 'publish' perhaps sounds more weighty and might make us think more carefully about what it is we are indeed 'publishing'.

Brake goes on to speculate that if, for example, the 'tweet' button was instead labelled "Tell 150 people and Twitter and any corporate organisations that in the future might want to search this something in 140 characters", we might pause and reflect more readily on what we are saying and sharing!

3/ According to Brake, what we do share, we share with an imagined audience; that is, our audience is in our heads and isn't necessarily the same as the actual audience we have (unless you are a professional who perhaps has access to and breaks down specific demographic data).

As such, we picture our audience, and we "talk" to the people we imagine are listening. Brake reckons this usually turns out to be the people we would wish to be listening to, which is potentially nothing like the audience we actually have.

In the case of this blog, I'm imagining you, the person reading it, are (in broad terms) an 'educator' of some sort—maybe a coach, teacher, or university tutor. Likewise, I'd like to think some of my students read it. Do you fit the profile of my imagined audience?

4/ Brake thinks we might often subscribe to a philosophy of "strength in numbers."

In essence, he believes that as so many people are posting and sharing stuff these days, we perceive that whatever we as individuals might share is just a drop in the ocean and will blend in with or get lost amongst all the other 'noise'.

However, Brake cautions that we should consider what might happen if what we share is picked up by someone with a much larger voice and suddenly our thoughts or comments that were meant in one context get taken and read in another. Indeed, it is impossible to predict the context in which our 'stuff' will be recirculated.

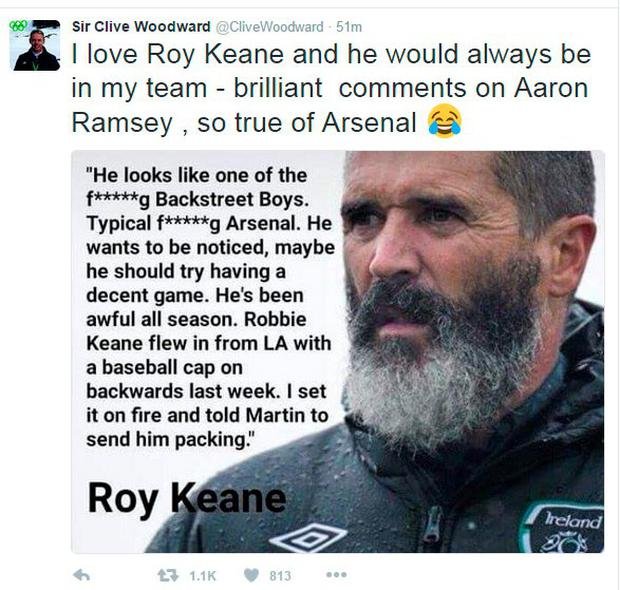

For example, on Twitter recently, rugby world cup-winning coach Clive Woodward 'tweeted' the below quote to his 91,000+ followers. At the time of writing, it had since been 'retweeted' nearly 2,500 times:

Now, I'm not sure where the original image or quote came from, but it turned out to be fake. Yes, Clive was guilty of spreading bullsh*t.

What might have originally been a joke or spoof 'meme' was now in a different realm. Yet who is most at fault, the person who created the fake quote, or the person or people who go on to uncritically spread it?

5/ Finally, according to Brake, the content we share on social media is getting what he terms "thinner and thinner."

He gives the example of the 140-character limit on Twitter, as well as the single images and increasingly shorter video clips that vie for our limited attention.

When seen in a particular light by a stream of people who might already know us, those snippets can mean one thing; however, when viewed in isolation, they can become something else completely or could be misinterpreted pretty easily.

Again, Brake suggests we tend to internalise the idea that we are talking to people who know us, because that's what we do in day to day life; however, we often don't (if ever) see the majority of people we interact with online "face to face,” we just have a mental vision of them.

Points for Reflection

Could (and should) we be better at acting as our own outgoing broadcast filter—a warning system that kicks in before we share information? In effect, better controlling the supply of information, rather than having to deal with it post-facto.

How might we do this? Brake suggests that before posting or sharing something, we should set it aside for 5 or 10 minutes and then come back to it and consider how it might be read by the people that conceivably could be reading it, who it might be visible to that we are not envisioning, as well as how it might be read in the future as well as now.

If we all did that, maybe less bullshit would spread, and our critical thinking shields would have less to filter.

N.B. I recently fell prey to the spreading of bullshit myself when I used the story of the Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis in a conference presentation. I was trying to highlight our reflex-like tendency to reject new evidence or knowledge if it contradicts established norms or beliefs; however, it turns out the story is a myth.